The Economic, Political, and Social Reasons Behind the Decision

Dispelling Common Myths About Nevada’s Gaming Legalization

Many people believe that Nevada legalized gambling because of mob pressure or a desire to become “Las Vegas.” The truth may surprise you.

Nevada experienced a boom-and-bust cycle as gold and silver mines flourished and faded just as California did after the 1849 gold rush. Unfortunately for Nevada, much of the state is covered in desert, while California could fall back on well-irrigated farmland and beautiful coastal areas.

When banks failed and the Great Depression hit, Nevada suffered from distressed agricultural prices, falling silver prices, and production. To boost interest in the state and invigorate the larger cities of Reno and Las Vegas, the Nevada legislature legalized open gaming. At the time, the only gaming mob was the four-man group of casino owners in Reno – all offering illegal gaming and prohibited booze.

Gambling was legalized as a practical economic response, not a criminal or glamorous decision, and its consequences reshaped Nevada permanently. Even today, casino gaming is the state’s largest industry.

Nevada Before 1931

Nevada was nothing but a stopover for several westward convoys in the 1800s. In the northern part of the state, wagon trains brought settlers from eastern towns like Dodge City, Kansas, and Independence, Missouri on 1200-mile treks to California. Some took the Oregon Trail, while some branched off through the Sierra Nevada Mountains on the California Trail, near Donner Lake, which brought the ill-fated Donner Party within miles of what became Reno.

The southern part of the state experienced wagon trains along the well-established Santa Fe Trail with outposts near what became Las Vegas. Few travelers made Nevada their home.

Still, some hearty souls who missed California’s gold rush at Sutter’s Mill in 1848 arrived in Virginia City, Nevada, to try their luck with the nation’s first significant silver deposit after the Comstock Lode was discovered in 1859.

As you can imagine, the thousands of men working Nevada’s silver mines – including the soon-booming towns of Goldfield and Tonopah – needed something to do with their time away from the mines, and their often good fortune. Gambling was a favorite pastime, second only to drinking.

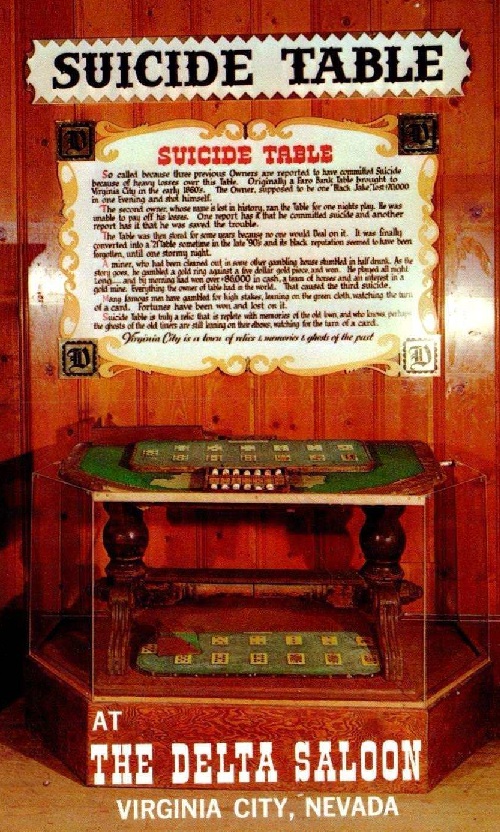

Gambling wasn’t regulated to any degree in Nevada mining towns, but from time to time, temperance groups got it shut down, at least temporarily. Virginia City was famous for mining riches, bar fights, and gambling. The popular game of Faro was offered at several bars in town, including the Delta Saloon, where a single table led to multiple deaths. It was dubbed the Suicide Table after three proprietors lost fortunes and their will to live.

In 1868, the final tracks of the Central Pacific Railroad through what would become downtown Reno were laid, about 38 years before the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad was finished. The latter, a 198-mile extension, connected to the mainline of the San Pedro, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake Railroad at Las Vegas and ran to the mining town of Goldfield.

Nevada’s Swooning 1920s and Decline

The 1920s were especially tough on Nevada. Mining towns became ghost towns as silver prices dropped and mines played out, and the state’s railroad importance dropped as the country fell to the Great Depression. It was assumed in surrounding states that you couldn’t even get a drink of alcohol in Nevada’s largest city, Reno, just when you needed one.

As Nevada’s population shrank, the state risked losing congressional representation. Cover Nevada’s shrinking population and risk of political irrelevance, including the threat of losing congressional representation.

Reno had enjoyed a thriving agricultural industry, and cattle grazed in multiple locations in the northern part of the state, but again, the depression loomed. Ranchers had loans called in, farmers struggled to finance farm expansions, and money was tight for most residents of the Silver State.

The Great Depression and Political Reality

After Wall Street fell, so did many banks in cities across the United States. George Wingfield, the wealthiest man in the state, owned the state’s largest banks. And when a bank manager embezzled $500,000 from the Reno branch, the local newspaper stories started a run on his bank. Wingfield’s empire was in danger. So was the state.

With no primary industry and no income tax, the state was headed to financial oblivion. In a last-ditch effort, state legislators introduced a bill to allow open gambling. There was no grand plan to boost Reno to the casino heights, or for Las Vegas to boom. The legislation legalized gaming, with local jurisdictions handling licensing and the state receiving a cut of net gaming income.

At the time, many states had outlawed casinos, even though they allowed games to be played. Reno had a provision that allowed gaming, including slot machines, as long as it was hidden from street-level view. Wingfield had multiple casino interests in Tonopah and Reno. Each was housed on the second floor of the building he owned.

State lawmakers chose legislative pragmatism on the second introduction of the gaming bill: survival over ideology. Assembly Bill 98, introduced by Nevada State Assembly Phil Tobin, was approved on March 19, 1931, allowing open gaming and ending the anti-gaming bill that had initially passed on February 24, 1909. A new six-week residency requirement was also approved for those seeking divorces. At the time, most states had residential waiting periods up to six months.

The 1931 Gambling Law

The legalization of wide-open gaming came with minimal regulation. Alcohol was not allowed on site, as the nation was still under Prohibition, the Eighteenth Amendment passed in 1919. But Truckee, California, and Reno, Nevada, were known for their excellent speakeasies where liquor was readily available.

Prostitution wasn’t legal on site either, but the Stockade of 44 rooms was two blocks from Reno’s downtown casinos. In Las Vegas, passengers stepping off the Union Pacific on Fremont Street were even closer to Block 16 with gambling, prostitution, and alcohol.

Although much of the nation disapproved, Nevada didn’t consider gaming any different from other legal businesses. The local Sheriff’s office handled gaming licenses in most towns, although some cities maintained a vote for/against any casinos. Reno maintained a red line district that the city council didn’t stray from for nearly a quarter of a century. If they had allowed casinos to sprawl beyond the downtown area, the city would most likely have grown nearly as fast as Las Vegas.

As for the passage of the original bill, Wingfield assigned his most powerful casino manager, Bill Graham, to rally local and non-local casino owners to support it. In this instance, rallying support involved raising funds to convince legislators that legalized gaming was a good idea.

Harold Stocker, owner of the Northern Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, quipped that he sent Graham a suitcase full of money. Stocker’s wife, Mayme, received the very first gaming license in Las Vegas with J. H. Morgan. Other early licenses were secured by Joe and Jack Murphy, Clyde Hatch, Walt Watson, “Pros” Goumond, and A. B. Witcher. The first five clubs included the Northern Club, Boulder Club, Las Vegas Club, Exchange Club, and the Red Rooster Nightclub.

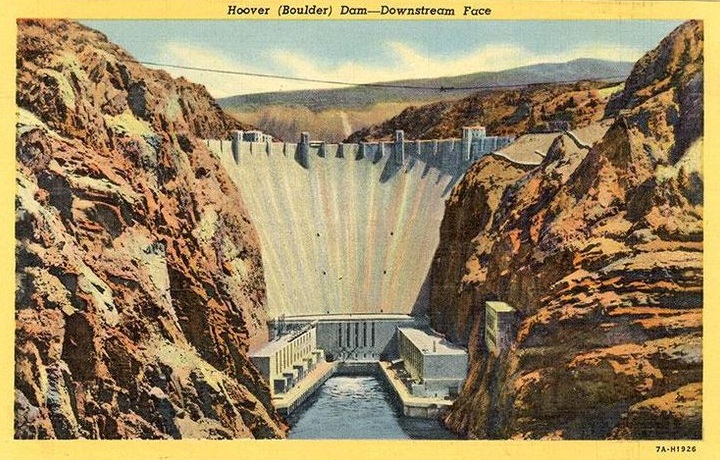

Downtown Las Vegas was already experiencing larger crowds due to the construction of the nearby Boulder Dam (later renamed Hoover Dam). Construction began in 1931, but planning and preparation began years earlier. The project required more than 21,000 workers, with 3,500 laboring daily. Las Vegas had a population of just 5,165 in 1930.

Why Organized Crime Was Not the Cause

Organized crime in the early 1930s was a real thing, but the Mob bosses of the time could not have cared less about the tiny clubs in Reno and Las Vegas. The Outfit in Chicago controlled liquor, prostitution, and gaming in the Windy City, plus a dozen towns nearby. Their bookmaking and casinos earned ten times as much as Nevada casinos did in the late 1920s. When the legislation was passed, the Chicago Tribune immediately ran a significant response with the headline, “CANCEL NEVADA’S STATEHOOD!”

Still, the prospect of legal casinos did give Mob bosses pause. The Outfit sent multiple associates to Reno and Las Vegas to gauge what was possible. Johnny Roselli looked at Reno’s casinos in the late 1920s and reported they were sawdust joints with little to offer.

Roselli, who had gone to work as a bootlegger for Tony Cornero in 1924, remained a lookout for racebook and casino opportunities in California for years. Still, the joints in Las Vegas paled to what Los Angeles offered.

Things started to change after gaming was legalized, with the New York Mob making a move against that same ex-bootlegger Tony Cornero. Evidence suggests Meyer Lansky was involved in talks with Cornero when his brother’s new Las Vegas casino, the Meadows, burned to the ground.

Local operators like Mayme Stocker and existing saloon owners gobbled up the early licenses in Las Vegas. Many other owners are featured in the book, Nevada’s Golden Age of Gambling.

Reno’s Bill Graham and Jim McKay opened their Bank Club in the Golden Hotel a month after legislation was finalized. They also operated the Rex Club and the Haymaker Club.

Across the alley, Giovanni (John) Petricciani was licensed for the Palace Club, a property he purchased in 1927. Nick Abelman owned the gaming at the Riverside Hotel, which George Wingfield owned. Abelman’s casinos in Reno and his gaming contemporaries are detailed in The Roots of Reno.

The Irony of Success

Although Nevada needed legalized gaming to attract visitors, lax enforcement for locals led to significant losses for the state. Tax laws and regulations on gaming income made casinos the perfect place to run organized crime. Especially after the early success of Reno and then the massive expansion of gaming in Las Vegas.

Early Consequences Nevada Did Not Anticipate

While Nevada’s coffers quickly filled up from gaming taxation, legislators were slow to enact any lasting oversight of casinos, owners, and outside interests. As the nation emerged from the Depression’s throes, Lake Tahoe, Reno, and Las Vegas became vacation spots, growing rapidly.

That pace and the influx of gangsters from the Midwest, like Baby Face Nelson and Alvin Karpis, kept Northern Nevada casino operators busy and infused with crime-ridden money that some managers were happy to launder. In fact, many criminals made Reno their home after robberies and kidnapping and told in the book Mob City Reno.

As the country went to war in the 1940s, local servicemen and women were stationed at multiple strategic locations across Nevada. Their dollars contributed to a rapid expansion of casinos. When the war was won, service people traveling across the country often stopped in Nevada to sample what they had heard stories about.

In addition, the US workforce changed drastically as women entered the military and service-type positions, raising household income to levels far higher than in the 1940s. Extra income often went to vacations. There’s a direct correlation between Nevada casino growth and higher income in the US.

The People Who Built Nevada Gaming

Visionaries, Hustlers, Legends, and Characters

Nevada’s gaming history is filled with unforgettable personalities — from casino owners and developers to gamblers, entertainers, and regulators.

Your site already contains rich biographies. This pillar page becomes the hub that connects them.

Related reading:

- [Casino owner profiles]

- [Famous gamblers and characters]

- [Regulators and political figures]

The Long-Term Impact of the 1931 Decision

Nevada’s decision to allow open gaming was a positive step toward shoring up the state’s financial woes. City and county tax rolls increased, and new administrative jobs opened. But construction trade jobs also boomed. As hotels and casinos opened across the state, workers had new jobs, leading to increased hiring in the casino and hotel industry.

Casinos in Reno and Lake Tahoe expanded, bringing experienced owners into the fray. Casino operators from the San Francisco Bay Area came first, followed by several from Kansas City, Chicago, and Joliet. Most had ties to organized crime and shared their profits with the Chicago Outfit.

The New York Mob was also involved but took a greater interest in Los Angeles and then Las Vegas. The book Vegas and the Mob clearly shows the links between dozens of casinos and organized crime, citing Congressional hearings, court cases, and, finally, Nevada State regulations that put an end to the illegal skimming of pre-tax profits.

Hidden Influence and the Birth of Modern Las Vegas

From the 1940s through the 1960s, organized crime played a major role in shaping Nevada’s early casino landscape. Mob‑financed casinos brought glamour, innovation, and high‑stakes risk.

Key figures included:

- Bugsy Siegel and the Flamingo

- Moe Dalitz and the Desert Inn

- Frank Rosenthal and the Stardust

- Tony Cornero and the Meadows

- The Chicago Outfit, Cleveland Syndicate, and others

Their influence eventually drew federal attention, leading to investigations, indictments, and the gradual decline of mob control.

Surprisingly, it took Nevada nearly two decades to strongly regulate its billion-dollar industry. First overseen by local government, the Nevada Tax Commission eventually sought to curb the misappropriation of income by casino interests. And, instead of a push to contain the massive income Las Vegas was enjoying, newspaper stories and the commission first concentrated efforts on small casinos in Lake Tahoe that weren’t even open 12 months a year.

In fact, it wasn’t until 1955 that the state Legislature created the Nevada Gaming Control Board within the Nevada Tax Commission, and its purpose was clearly articulated: to develop a policy to eliminate the undesirable elements hidden within Nevada casinos.

Four years later, the Nevada Gaming Commission was established, which is primarily responsible for overseeing licensing matters. As organized crime took over multiple casinos, the state did its best to root out hidden ownership. Still, it was a slow process that took over two decades and cost the state and US government hundreds of millions of dollars that went to crime families.

Conclusion on Nevada’s Open Gaming Laws

Although unpopular in many states, Nevada’s decision to buck national views and allow open gaming was a pragmatic survival decision. It also opened the door to decades of booming visitors and a thriving entertainment industry.

In a national context, Nevada took advantage of its wide-open spaces and low operating costs (including land purchases). It developed a gaming culture that transformed Southern Nevada’s desert into prosperous vacation destinations and put hundreds of thousands of future residents to work in well-paying jobs.

The Rise of the Casino Resort

Corporate Money, Mega‑Resorts, and a New Era

As mob influence faded, corporations stepped in. Howard Hughes’ buying spree in the late 1960s reshaped ownership norms and opened the door to publicly traded casino companies.

In Las Vegas, the 1980s and 1990s brought the mega‑resort boom:

- The Mirage

- Bellagio

- Mandalay Bay

- Luxor

- New York‑New York

These properties transformed Las Vegas into a global entertainment destination. Reno and Lake Tahoe followed their own paths, adapting to shifting tourism and economic trends.

Related reading:

- [Howard Hughes in Nevada]

- [The Mirage and the mega‑resort era]

- [Reno and Tahoe casino evolution]

Beyond the 1931 legislative acts, one short law reshaped Nevada’s identity to one of freedom of choice and independence. Nevada remains a no-income-tax state with many fine residential areas, quality schools and colleges, and a strong job market.

For a deeper look at the casinos that emerged after legalization, see our recommended books.