L. M. Strauss, a native of the San Francisco Bay area, was born in October 1904. Growing up, he was like any other youth in the area, driven by the desire to earn some extra cash to support his interests and socialize with his peers. His early exposure to poker, particularly five-card stud, and his willingness to engage in dice games showcased his early affinity for risk-taking and his adaptability to different situations.

At sixteen, he formed a close-knit team with Jeri Feri and Tony Cornero Stralla. Together, they embarked on a daring venture, stealing cases of illegal booze and selling them to restaurants and rival bootleggers. Strauss, tall and wiry, often looked down on his partners, but he was no gang leader. Their shared experiences and camaraderie were the backbone of their operation.

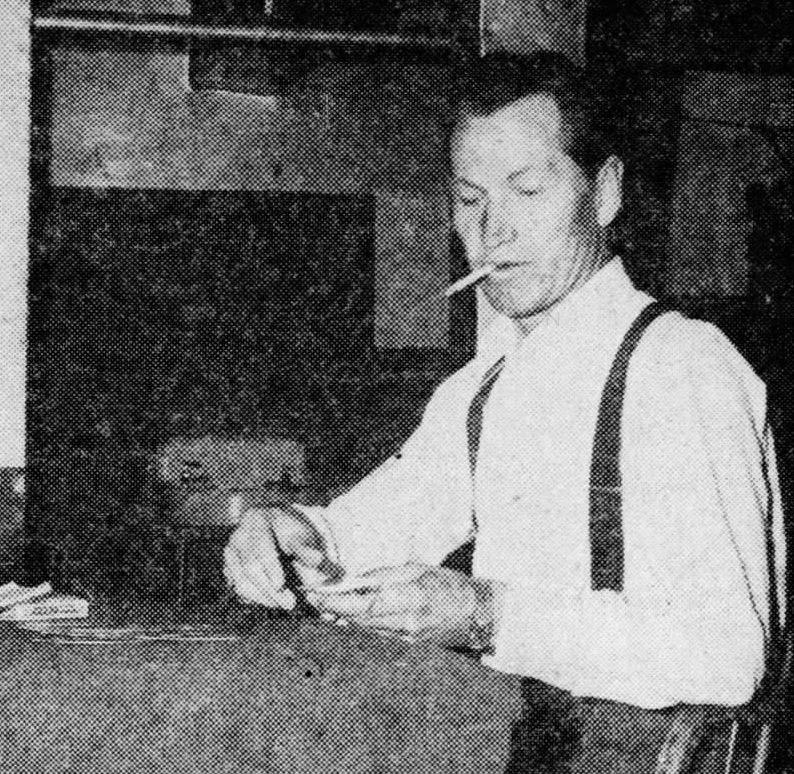

Each member of Strauss’s team had their own distinct personality. Tony Cornero, with his love for extravagant hats, earned the moniker “The Hat.” James Lanza, known as “Jimmy the Hat,” Had his own unique charm. Strauss, with his stylish wave of black hair, was dubbed “The Russian” due to his Latvian heritage. These monikers not only added color to their characters but also reflected the diverse backgrounds of the team.

While his friends took to rum running and great wealth, Strauss took a different path. He forced his way into partnerships with small Italian restaurants around Fisherman’s Wharf, often rubbing people the wrong way. But it was part of his charm, a mysterious allure that drew people to him despite his rough edges.

The Russian was an upstanding citizen in San Francisco, even after being arrested for stealing goods from the docks and robbery. He was charged with shooting a rival bootlegger but did only a short time in jail when the injured party refused to press charges.

The End of Prohibition

When Prohibition, a period that had been a lucrative time for bootleggers, finally ended, it brought about a seismic shift in the underworld. Strauss, a partner in two bars in the Bay Area, found himself on the wrong side of this change. His falling out with Genaro Broccolo and James Lanza and Cornero’s subsequent imprisonment marked a significant turning point in his life. Cornero’s decision to open a casino in Las Vegas upon his release was a clear sign of the changing times.

Strauss also wandered to Los Angeles, where he worked for Farmer Page at an illegal casino and met Charles Howe and Billy Burns. In October 1934, the friends headed to Las Vegas, a tiny town with just five small casinos on Fremont Street.

After casing the competition (Apache, Big Four, Boulder, Las Vegas, and Northern), Strauss and his buddies settled on Elmer Sorber and Dave Stearns Northern Club as their mark.

Howe asked to speak to the owners, showed he could deal the game Faro from a cardholder case, and offered to go partners at one of the tables. They arrived at a one-third split, each banking the game for $1000, and Howe started dealing the game soon afterward.

Howe’s time in the casino was short since one of his early players was his friend Billy Burns, who racked up $3200 in winnings before Stearns came rushing into the club after being told by his manager that the Faro game was blowing up.

Stearns told Howe to close the game, took Burns to a far corner, and said he could only give him $800 but promised the rest in a few days. Then he asked Howe for his $1,000, and Howe refused, saying Stearns and Sorber should pay the first $2,000 and they should make a deal with Burns.

When Burns arrived the next day, the parties agreed on $2,000, with $1,200 coming in two days. But by then, Sterns and Sorber knew who Burns, Howe, and even Strauss were.

In the end, even after the crooked gamers from California protested at a City Hall meeting, they only made another $200 profit, leaving with a total of $1000 and a threat never to return to the city.

Back to the Bay and Beyond

Strauss returned to the Bay Area and worked for Frank “Dingo” Mesdoza at the Clover Club in Palo Alto, stopping only after the casino was closed. He was sentenced to 60 days in prison and a $250 fine for dealing 21.

He spent the next year managing the Casa Manana nightclub on El Camino Real just outside Palo Alto. Then he moved to the Menlo Club and worked with Elmer “Bones” Remmer.

In 1939, Bugsy Siegel pushed Tony Cornero for 25% of his profits from the SS Rex parked three miles outside Santa Monica Pier in California. Through unknown contacts, Siegel and Mickey Cohen convinced Strauss to rob Cornero’s gaming ship.

According to Strauss, the robbery was successful, giving him a nice chunk of cash.

Still, by the mid-forties, he had worked for Bones at the Cal-Neva Lodge at Lake Tahoe and the Green Shack in Las Vegas. But somehow, he came up with enough cash to buy into a partnership at the Tahoe Village casino for the 1947 summer season.

His partners included Abe “The Trigger” Chapman, George “The Professor” Kosloff, and Sam Houser. If we know The Russian’s usual tactics, they put up the lion’s share of the cash. The group partnered with Harry Sherwood, a 230-pound ex-boxer and restauranteur from San Francisco. The Lake was packed that summer. Casinos were busy, and the Tahoe Village was raking it in. But nobody was getting paid.

By the 12th of September, as the season wound down, the employees were due two checks. Suppliers were waiting for payments, and so was the county—not to mention Fred Wilkins, Jim, and Denny Wood, who owned the building!

On the 13th, while Louie and Harry Sherwood were alone with the books in executive offices, the other partners waited at the bar. A single gunshot pierced the quiet of the closed casino, and Louie entered the bar area. In the office, Sherwood was bleeding from a gun wound through his arm, and a bullet lodged near his spine.

The Russian left the building, went home, packed his clothes and 18-year-old girlfriend in his car, and attached it to his motorhome. He was captured 10 miles away.

The Aftermath of a Deadly Shooting at Tahoe Village

Although the Russian acted alone, his partners were detained for aiding and abetting. Sherwood was hospitalized. Louie swore Sherwood had plundered the cash reserves to the tune of at least $80,000. When confronted, he had punched The Russian, who drew his .38 caliber police special revolver and shot him in self-defense.

Later, Louie’s partners swore they were in the room, and it really was an act of self-defense. On October 3rd, Sherwood died, and Justice of the Peace D W McCleery stated there was no reason to press charges as the defensive act was justified. All suspects walked. McCleery retired soon afterward.

Russian Louie Strauss moved to Las Vegas afterward and was involved in an incident at the Club Savoy after Norman Khourrey, a Cleveland gaming owner, bought the club. Along with Allen Smiley (who was alone with Bugsy Siegel when he was gunned down in Los Angeles the year before) and Jack Durant, Louie gets loaded dice into a game Bob “The Fixer” Smith is running at the club.

Eventually, the crew wins $67,000, and the club can only pay $20,000 (sound familiar?), but the Russian walks free as usual. The loaded dice disappeared.

Incensed by what she reads about the event at the casino, Harry Sherwood’s widow sues Strauss for $750,000. Although the case is thrown out, it soon reappears, and she is finally vindicated with a $150,000 verdict against Strauss. By then, he is dead.

How Did Louie “The Russian” Strauss Die?

Although Strauss seemed to think he was invincible, the end did come. It probably didn’t have anything to do with Benny Binion, owner of Binion’s Horseshoe casino in Las Vegas. But that doesn’t mean Binion wasn’t prone to setting things straight!

Strauss may have tried to blackmail Benny; at least, that was the word of Jimmy “The Weasel” Fratianno, a mob killer. But who can you trust to tell the truth these days?

While strong-arming investors in an apartment complex and shooting dice, Russian Louie loved to play poker. After taking a $12,000 marker at the Flamingo, Gus Greenbaum told the Russian that he now owed the club $42,000—which included the $30,000 Chicago wanted from their part of the “losses” at the Tahoe Village when $80,000 went missing—no matter what happened in the back room.

Strauss paid the $12,000 but refused to take responsibility for the missing $80k. The next day, Strauss played in a private poker game and won $75,000 with some deft hands. Did he cheat? Probably. Did he pay Chicago through the Flamingo? Nope.

Tony Accardo isn’t happy. He talks to his enforcer in Vegas, Marshall Caifano. Caifano tells Louie they should head to Palm Springs, where the rich poker suckers are.

At the last minute, Marshall says he can’t go, but Milwaukee Phil Alderisio wants to go. According to Jimmy “The Weasel,” he picked them up at Louie’s place in his new Cadillac.

They drive to a cabin an hour outside Palm Springs for a rest at a guy’s house who owes Phil some cash. They go inside, where Frank Bompensiero introduces the Russian to a garrote, strangling him to death. Louie takes a dirt nap and is never heard from again.

Although the Russian is gone, his estate is attached for the $150,000 judgment, and strangely enough, a woman in Ojai, California, Elsie Jones, winds up in a court fight over a new 1953 Cadillac, which she possesses and says she paid for. His brother, Matt, says the title is in his name and was paid for with money Strauss gave her. Even in death, where the money came from for any of the Russian’s deals is again in question.

Leave a comment